The Man Who Taught Me to Fish

The summer I turned 13, my father took me steelhead fishing on the Klickitat River in Washington. By then I figure he had put in hundreds of hours, patiently teaching me to fish for those noble creatures.

On this particular day, I guess my apprenticeship was over. We got out of the car. He scanned the blue-green water. “You fish around here,” he said. “I’m going upstream.”

I sensed a turning point. Maybe even a rite of passage. He rarely let me out of sight on powerful rivers like this, because I had a well-earned reputation for wading with all the grace and circumspection of a bull moose in rut. Which was why he always positioned me upstream, within viewing range, so he could grab me as I drifted by. But oddly, not this morning. Nor did he deliver the usual wisdom about what bait or lure to use, or what pool to fish or how to fish it. I didn’t even get his typical warning about rattlesnakes, for which the Klickitat was notorious. Yep, I was clearly on my own.

So off we went, the Old Man trudging up the trail while I, with some trepidation, slid down the bank to the river. I found a pool that my limited experience told me might hold a steelhead. I remember that heady feeling of independence and adventure. The smell of the cold water in the desert air, negotiating such a big, gorgeous river and trying to figure things out for myself. As he had taught me, I took time to observe the swirling currents. The rocks. The various depths and channels. I tried to think like a fish rather than a hormone-addled teenager who was beginning to think about a lot of things other than fishing.

A few casts later, I somehow hooked and landed a bright, summer-run steelhead that might have weighed four pounds. It was small by Klickitat standards, but I surely didn’t care. I was giddy with joy and pride, because up to that point I had never caught a steelhead without my father’s streamside guidance. And I was certain that, because I had caught it so quickly, I had for once in my young life out-fished the old fart. It was a monumental day. A milestone.

I headed upstream with light steps, beaming, to show off my trophy and let the Old Man know I had matured into his fishing equal. That I had become a true fisherman and maybe even a man. I came around a bend in the river, and there he was. He walked towards me, dragging a steelhead so big it looked like he had found a chrome Cadillac bumper on the bank.

I looked at his fish. I looked at mine. I looked back at his, guessing it might have weighed eighteen pounds if not twenty. I was deflated. Defeated. Crushed. Compared to that fish, mine looked like something I’d pulled from a Safeway seafood case.

My Old Man had never been the sensitive type. But I could tell he felt badly and understood why I looked like my cat had just been run over. He congratulated me profusely, telling me how well I had done, how proud he was, how he had just been plain lucky and blah blah blah. We set both fish in the grass to take a photo. It looked like his had just given birth to mine.

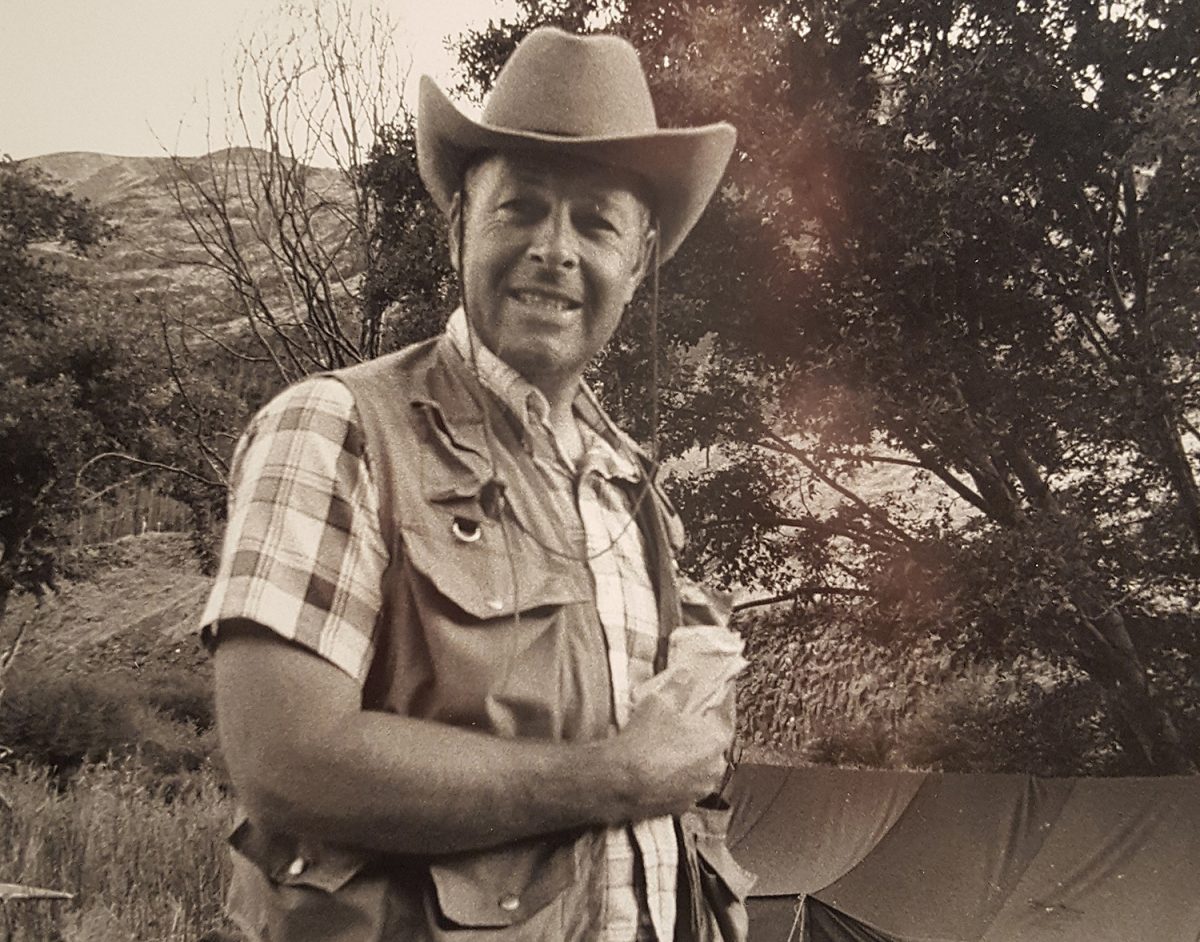

Hal Dove on the Deschutes River, late 1960s.

Through the ensuring years and decades, we would retell the Klickitat story many, many times—to ourselves, to family and friends, to anyone who might listen and who, having heard the story more than once, usually rolled their eyes. He and I would laugh, knowing that something very special had passed between us that day. It would be my great fortune to have many memorable days with the Old Man. Fishing. Hunting. Identifying a new bird. Observing a mule deer buck at sunrise. Discussing tackle over a snort of single malt scotch.

But we were only so close. My father never once told me he loved me. He never hugged me, nor I him. He expressed his love by teaching me to fish and hunt, as was his relationship with my older brother. He helped us learn the birds and mammals and to revere them. To sit on the bank of a river together and simply listen to eternity. Then I could see the love in his eyes, and it had to be enough for me.

Sadly, my sister received far less because my father was old-school. In his generation, girls just didn’t go fishing and hunting. He clearly adored my sister, but I believe her childhood was short-changed because the Old Man had few other outlets for engaging with his kids or expressing his love for them.

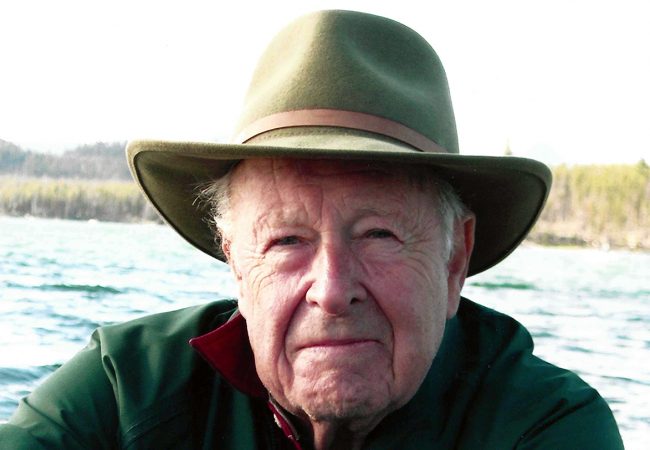

Hal Dove passed away in September of 2009, forty years after that day on the Klickitat. The afternoon that he died, in his own bed, the Townsend’s Solitaires were trilling in the junipers outside his window. Just a few months before, he and I had sat on his deck at dusk and observed the silhouette of a great horned owl as it hooted from one of those same junipers. “These are the important things,” he said, shaking a fist for emphasis. “These are the things I treasure.”

It seemed the moment pleased him as much as anything had ever done. Maybe as much as that day on the Klickitat.

Over the years, I’ve concluded that this man’s gift of fishing and nature may have saved my life. There was a dark phase in my early adult years, a painful era defined by confusion and depression, complicated by a head injury and a poisonous lifestyle to keep from dealing with any of it. I held the darkness mostly to myself, because our family creed was to never show emotions or weakness. In my father’s words, we were to “pay attention to business” no matter what. We were to appear strong, even if we weren’t, and get on with it.

But perhaps the Old Man knew more back then than I thought. There were certain nights when I was home from school on breaks, when I’d stumble in toward dawn, lost and so far from the innocence of that wild-eyed boy on the Klickitat river. I’d flop onto my old childhood bed, my thoughts jumbled up without any clear answers to the questions that had pushed me to that abyss.

Then I would hear a knock on my bedroom door. “Get your gear together,” a strong voice would say. “We’re going fishing.”